You’d feel kind of tricked, right? Like you just wanted to read an article and instead, you’re being sold Amazon products or a specific pasta brand just so that the website can rake in a tidy profit from a particularly sneaky form of advertising? Sponsored content is becoming more and more prevalent as more publications — even the most prestigious — accept and even promote sponsored content. This is perfectly understandable, as media companies are under intense economic pressure and are looking for new revenue streams just to stay afloat. But does sponsored content do readers a disservice? And in so doing, are companies making a mistake going in this direction if it risks alienating their customers and potential customers who might feel had?

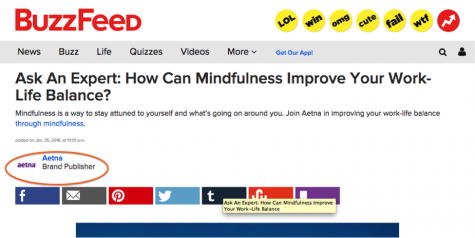

When you see an ad on TV, in print, or on a website, you know you’re looking at a paid message. With sponsored content it’s not always obvious that what you are reading or looking at has been sponsored by a third party. Do publishers have to disclose when content is sponsored? Legally speaking, yes. According to Federal Trade Commission, publishers are required by law to disclose any “material connection” to a brand. Even a one sentence Tweet should include the hashtag #sponsored or #ad. The FTC gives publishers detailed guidelines about how, when and where to disclose this info. Unfortunately not everyone follows these laws – indeed, many big publishers hide their disclosures in order to blend their paid content in with their non-paid content, sometimes called native advertising.

Relatively new media companies such as Buzzfeed and Vice offer a diverse amount of “special content” and have been followed by blue chip media companies such as the New Yorker, which has branched into sponsored content in recent years, and the New York Times, which launched a branded content studio a few years ago called T Brand Studio.

Sponsored content has a place in the “marketing mix,” so long as the media outlet clearly delineates journalistic content from that which is paid for. We’d also note that just because you’re paying for it doesn’t mean you are now free to promote your brand, product or service…we’d argue that it’s all the more imperative that you take an even-handed, reportorial approach, erring on the side of providing information and insight versus bald touting of your awesomeness. As in most things, we recommend you just let your awesomeness emerge organically.

Bear in mind that BackBone specializes in “earned media” — getting clients coverage in credible media outlets on the strength of your story. This is still the most persuasive type of “messaging” as it’s either a reporter writing objectively about your and your company…or a bylined “thought leadership” article written by your or your CEO that’s almost entirely informational (with some degree of editorializing). Getting into a Forbes or Crain’s is hard, and sponsored may be the surest route; ideally, you’d be able to develop a portfolio weighted toward earned media, with key “gets” via sponsorship.

We’ve worked with companies in developing sponsored content and believe it does have a place — but there are caveats and considerations. Ultimately, sponsored content works best when it’s “backed” by the credibility and third party validation that comes with “earned” media.

Leave a Reply